Modern espionage literature is rife with authors who once plied the spy trade. Ian Fleming invented James Bond after his World War II service as a British naval intelligence officer. David Cornwell, better known as John Le Carré, was still working for MI6 when he penned his first espionage thriller, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. And former CIA operations officer Jason Matthew's experience dodging Russian KGB surveillance teams in Moscow deeply informs his Red Sparrow trilogy.

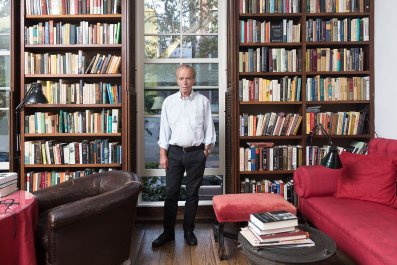

Then there is the veteran Israeli espionage journalist Ronen Bergman, who has taken a slightly different angle into the shadow world of spies, counterspies and assassinations. Drafted into the Israeli Defense Forces in 1990, Bergman spent three years recruiting and handling informants for the army's criminal investigative division, where he burrowed into military corruption, drug trafficking, arms dealing and other crimes. The skills he learned there have served him well as Israel's premier chronicler of the country's principal spy services—the Mossad (Israel's CIA), Shin Bet its (internal security organ) and Aman (military intelligence).

"I think that the training and experience with the recruitment and running of live agents, whoever they are...gives you [insights into] their situations…and their mindset," he said during an interview to promote his latest and much anticipated book, Rise Up and Kill: The Secret History of Israel's Targeted Assassinations.

Like most Israeli men, Bergman, 45, still serves in the army reserves and is obligated by law to do so until he reaches the age of 51. But there's no cross-pollination between his military service and his reporting on Israeli intelligence, he says: "I do not report about things that I do, and I'm not involved in anything that is connected to what I am reporting about. There's a total separation of these two worlds."

Nevertheless, his intelligence credentials have no doubt helped him gain the trust of Israel's spymasters and operatives. As the senior political and military analyst for Yedioth Ahronoth, Israel's largest-circulation daily, his columns and books (nine now) have regularly exposed internal debates of the nation's intelligence agencies, making him a must-read for national security geeks the world over. For Rise Up, he interviewed "over a thousand" current and former officials, plus others, he said.

The book catalogues Israel's six-decade history of "negative treatment" (the Hebrew euphemism for targeted killing operations) against its enemies, which, over time, ranged from fugitive German war criminals and rocket scientists to front-line Arab leaders to Iraqi nuclear officials (under Saddam Hussein) and then scientists in Iran's nuclear program. And always, of course, there were the Palestinian leaders, and later Iran-backed Hezbollah militants, to be "liquidated."

One reviewer said Rise Up (taken from the Talmudic instruction, "If someone comes to kill you, rise up and kill him first") begins to read like "an endless police blotter [of] Israel's greatest hits." But over some 750 heavily footnoted pages, many top Israeli officials confess to moral qualms, foul-ups and mistakes—killing the wrong person or innocent bystanders, or murdering a Palestinian leader who might have made a good partner in peace negotiations.

Related: How Israel won the war

I asked Bergman if he came across anything really surprising in his research. Yes, he said quickly. "One day I was sitting in a north Tel Aviv café, not far away from where I live, with someone from the Air Force, and we were discussing all sorts of different topics. And he said, 'I have something I need to relieve myself of, that I kept for so long.'" It turned out to be the extraordinary story of how, in 1982, on orders from then-Defense Minister Ariel Sharon, Israeli pilots nearly shot down a civilian plane because of a Mossad team's mistaken belief that Palestine Liberation Organization leader Yasir Arafat was aboard it. Only a last-second correction by Mossad operatives saved the lives of the passengers, which included Arafat's look-alike younger brother, Fathi, a pediatrician and founder of the Red Crescent, and 30 wounded Palestinian children he was taking to Cairo for medical treatment. The incident was recounted in a January 23 excerpt in The New York Times. In the book, Bergman hints that Sharon, who was long obsessed with killing Arafat, might have authorized his fatal poisoning in 2004. But even if he knew it to be true, he writes, "the military censor in Israel forbids me from discussing the subject."

"For the last two decades," Bergman told me, "I am in constant struggle with Israeli military censorship and the Israeli administration." He has been called in for "a few interrogations," and authorities have issued "indictments against my alleged sources," he said. In 2010 and 2011, the army chief of staff "demanded the attorney general to open an inquiring investigation against me for high treason. They have been fighting fiercely against me and my work."

But Bergman had gained many allies for his probes, especially within the Mossad, it appears, whose recent leaders have feuded, sometimes openly, with the right-wing, pro-settler administration of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. It's not surprising then that Tamir Pardo, just one of the former Mossad chiefs who were sources for Bergman, praises Rise Up. It's "the most impressive book I have seen on the subject and the first one written using real research rather than a fictional narrative," he said in a blurb for the book.

The Mossad, of course, has loomed large in fiction. One of the biggest myths, depicted in Steven Spielberg's 2005 film Munich, was that its agents hunted down and assassinated the Palestinians who carried out the murder of 11 Israeli athletes and a German policeman at the 1972 Olympic Games. In fact, he says, "Most of the people who were involved in Munich were never killed or caught. The Mossad started to kill whoever they could. The people that they killed—most of them—had nothing to do with Munich. "Spielberg's film, he says, was based on a book that relied the account of an Israeli who claimed to be the lead assassin of the hit team, but in reality was "a baggage inspector" at the Tel Aviv airport.

But kill they did, "liquidating" scores of targeted Palestinians over the ensuing decades. It also launched ruthless operations against Hezbollah, most notably the group's terrorist mastermind Imad Mugniyah, whom it took out with a car bomb in coordination with the CIA in 2008.

When it comes to assassinations, Bergman says, the sheckle stops at the prime minister's desk. It is not a "rogue agency." Israeli intelligence dispatches hit teams with the approval of the prime minister and, it seems, the overwhelming approval of the Jewish nation.

But the intelligence community doesn't always agree with the prime minister. In the run-up to Israel's 2015 elections, Netanyahu stoked fears of an Iranian nuclear bomb and strongly hinted Israel would preemptively attack Iran's nuclear program. Netanyahu even held several military exercises to underscore his intent—moves that prompted some former intelligence chiefs to warn the country against what they regarded as his excesses.

"Wake up!" implored one of the Mossad's most ruthless former chiefs, Meir Dagan. Fiercely opposed to Netanyahu, he prayed that "Israeli citizens will stop being hostages of the fears and the anxieties that menace us morning and night."

Related: How the CIA took out Hezbollah's Imad Mugniyah

In the past, pronouncements by such august Israelis would be treated as "sacred," Bergman writes. But no longer. "The strength of the old elites has ebbed," he says, "New elites—Jews from Arab lands, the Orthodox, the right wing—are in ascendancy." Moderation is out, extremism is in. Israeli leaders claim an absolute right to the occupied West Bank and all of Jerusalem. The Orthodox parties in the ruling coalition campaign for a Jewish theocracy over an Israeli democracy. The same often goes for Israel's Mizrahi Jews, many of whom were expelled from their Arab homelands when Israel was created in 1948.

If anything, there's more popular support than ever for the security agencies' robust elimination of both external and internal threats. The problem is that none of its tactical victories has brought Israel anything more than a temporary reprieve from immediate threats, much less peace. The cycle of violence, now in its seventh decade is not likely to abate considering the turmoil in Syria and Iraq, rocket attacks from Gaza, missile threats in southern Lebanon and the menace of Iran. Of the many ironies in Bergman's often-riveting accounts is that several Mossad, Shin Bet and Aman leaders have emerged after their blood-soaked tours of duty to say enough is enough.

"I call it the banality of evil," former Shin Bet chief Ami Ayalon told Bergman, echoing the outspoken sentiments of six former security agency chiefs in the extraordinary 2012 documentary, The Gatekeepers. "You get used to killing. Human life becomes something plain, easy to dispose of."

And what did it accomplish?

"We wanted security," Ayalon said in 2012, "and we got more terrorism."

With Jonathan Broder in Washington, D.C.